|

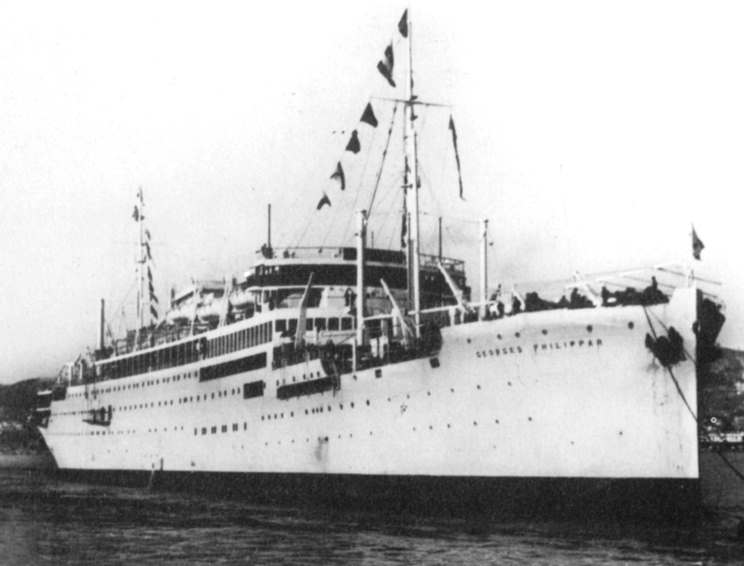

The Georges Philippar was the Messageries Maritimes latest liner, she had the latest safety and luxury fittings that a liner of the early 1930's could have. She was built to replace the Paul Lecat, which was destroyed by fire on Dec. 30, 1928, but the Georges Philippar was not even completed before it caught fire. On November 29, 1930 while fitting out a fire started in the cold storage area which caused "considerable" damage to the ship, however the majority of the luxury fittings had not been installed, so financial damage was less that it would have been in another month. By February the ship had been repaired and was made ready for her maiden voyage. Before the ship left the French police received intelligence that the new ship was to be blown up in the Suez canal in an attempt to block the waterway. Some believed that the ship was carrying munitions to Japan to be used to fight the Communist in China, but this was apparently not true, The ship was searched, but nothing was found and her maiden voyage from Marseilles began without delay on Feb. 26, 1932. When she arrived at Port Said she remained only a short time and then sailed through the canal without incident. She arrived at Yokohama, Japan on Apr. 14, but because of some civil unrest she did not remain long and soon she was off on the return leg. She touched at Shanghai, then Saigon and finally Colombo, during the voyage an alarm in a strongroom containing a large amount of gold bullion went off on two occasions, both times it was investigated, no evidence of tampering was found and "no accountable reason" was found for the alarm, nothing more was thought of this. The second time this occurred according to the master was about 1:30 a.m. on May 16, 1932. At about 1:45 a.m. as the ship approached the Gulf of Aden on May 16, 1932 a fire was reported in the cabin of Mrs. Valentin, the wife of one of the engineers. She reported the fire, which was on D deck amidships, and several crewmen set about to put out the flames. At first the crew thought that they could suppress the flames in short order and therefore did not inform the master. After 30 minutes those who were fighting the fire realized that it was out of control and the master was finally informed. The second officer ordered full steam ahead in an attempt to beach the ship, but this caused the ventilation system to fan the flames even more. Even with the latest fire fighting equipment installed, the flames grew faster than expected, it was later reported that more fires broke out in adjoining staterooms, possibly along the same electrical circuit which had caused the original fire. With the flames being fanned by the speed of the ship, the passageways became filled with smoke and fire and a number of passengers rapidly became trapped in their cabins. Warning all on board was done room by room as the alarm system was cut off when the chief electrician cut the electricity to prevent further fires breaking out and due to this some people who might have been saved perished in their cabins. Some watertight doors were also closed cutting off escape for even more. Up on the boat deck there seems to have been a certain amount of order in getting everyone off the ship, of course there was some panic, people were said to have returned to their rooms in search of valuables, which cost them their lives, others jumped overboard rather than wait for the boats to be lowered, again at the cost of their lives. A Dutch doctor named van Tricht was said to have made his way to his cabin where his children had been sleeping only to find the room afire "like a furnace" that nobody could have survived, other survivors told of the horrors of hearing the screams of people who were trapped in their cabins dying or about to die, sounds no human can ever forget. Even with all this tragedy the majority of those who made it on deck were saved mostly thanks to the coolness of the captain and crew, according to statements made at the time by those who survived the terrible ordeal, but this would change. The lifeboats were loaded in the tradition of the sea, women and children first, men then the crew followed by the officers and the master last. Captain Vicq left the ship at 8 a.m. after personally checking all first and second class cabins that were accessible. Captain Vicq was burned in the face and legs, but he still supervised the rescue of his passengers from a lifeboat. The S.O.S. had been sent shortly after 2:15 a.m., but the signals did not last long as the generator which powered the radio shack was disabled by the fire soon after it started. Even so three ships responded, and as the fire burned bright in the clear night sky the scene of the disaster was easy to find. The first vessel to arrive was the Russian tanker Sovietskaia Helt, followed shortly thereafter by the British freighters Contractor and Mahsud. While all three rendered assistance, the Russian ship picked the bulk of the people from the sea. The three ships departed leaving the Georges Philippar to her fate and headed for different ports. The two British ships made for Aden and arrived on May 17, Contractor unloaded 132 survivors and Mahsud another 120 or more. Several had died en route and were buried at sea and others were taken straight to hospital because of the serious of their injuries. The Russian ship made for Djibouti where it transferred 420 survivors to the André Lebon for transport to Aden. Since the total number of people onboard was not known for sure, the number of deaths has never been confirmed, early reports placed the number between 50 and 100, but the figure officially agreed to later was 49, the number of survivors was about 676 in all. Among those who were lost was the French journalist Albert Londres, who had written about, among other subjects, the French prison bagne de Cayenne (Devil's Island), he was returning from China where he was writing a story about a murder. There were two other victims related to the ship who were not even onboard, the record setting French aviator Marcel Goulette and his co-pilot Moreau. They were sent to Brindisi to pick up Alfred Lang-Willar, an officer with Louis Dreyfuss & Company, and his wife and fly them home. They left Brindisi on May 26 bound for Marseilles via Genoa and Rome, but the aircraft never arrived. The wreckage was found on May 29 in the Ernici mountains about 60 miles south of Rome, it appears that due to very heavy overcast the plane flew full speed into the side of the mountain, nobody survived. In Dec. of 1934 the jewelry belonging to Mrs. Lang-Willar turned up at a jewelers in Lyons, they were brought in by an Italian laborer who recovered them from the crash site and were valued at 300,000f. The man, supposedly had no idea of the value of the jewelry, and gave it little thought, the police at that time said they believed the man and would not prefer charges. The survivors were taken to Marseilles by the P&O liner Comorin and arrived on May 27, but they were delayed from disembarking the ship due to a case of smallpox which was found. The Georges Philippar continued to burn until May 19 when at 2:56 p.m. the most modern ship in the French merchant fleet succumbed to the sea. In July 1934 the crews of the two British ships which came to the rescue of those in distress on the Georges Philippar were awarded the Medaille de Sauvetage, one of the highest awards given by the French for lifesaving at sea. The medals and diplomas were presented to the men at Liverpool by the French Consul General Maurice Charpenter with the Lord-Mayor of Liverpool presiding over the ceremony. The masters were awarded gold medals and the crews were awarded silver medals, this was the only positive event that happened following the sinking. The investigation that followed showed that the disaster was avoidable, but it took some time for this to come to light. The ship was insured mostly by British companies and these underwriters paid a claim for £1,250,000 to the Messageries Maritimes within a week of the disaster, this with no evidence to suggest that they were not liable for the loss, but there was a caveat, the insurance companies would pay only with the understanding that they would be provided with a copy of the official report when it was completed, this was so they could assess the cause and better determine if they were in fact liable for the losses. The report was finished on Aug. 6, 1932, but it was not forwarded to the insurance companies in England, and by July of the same year the insurance companies had made the unprecedented move to request the return of the funds paid to the ship owner. About the same time over 40 people brought suit against the Messageries Maritimes for the loss of their loved ones. Before any of this was settled there would be another French passenger ship destroyed by fire. On Jan. 4, 1933 the new liner L'Atlantique, while en route from Bordeaux to Le Havre caught fire in the English Channel, she carried no passengers, but 19 crewmen were killed in the fire and the ship, while towed to Cherbourg, was a total loss. The fire started in a passenger cabin and was caused by the electrical system, just as in the Georges Philippar. While she was not owned by Messageries Maritimes the concern was that French built ships had faulty electrical systems. It took until May of 1933 before the insurance companies received a copy of the report and even then some documents were omitted by the Ministry of Marine in France, but it was concluded that the fire was caused by a fault in the electrical system and that many of the resulting deaths were due to the incompetence of the master and crew. In 1934 the master, 2nd officer and two crewmen were charged with manslaughter, with them over 20 company officials, government inspectors and officers of the ship's builder were also charged. At this time I have not been able to learn what the judgment in their cases were. |

© 2011 Michael W. Pocock MaritimeQuest.com |

|

Georges Philippar seen shortly after completion. |