I was fortunate [I think] to be accepted into the Navy - which was where in some sort of romantic fashion I wanted to go. Only a minority were given that chance. I'd always liked idea of going to sea. To be accepted for 'the Andrew', it helped in 1947 to have your Higher School Certificate (Now A Level); and the promise of a university place after service. I was told I would be trained as a Radio Mechanic; but found that priorities were changed and I was allocated to the signal department (they were reasonably sure that I could read and write

fluently).

Those who were called up as group 101 in January 1947 have every reason to remember their initial training. You always remember two things, one is the date when you joined up - in any case 13th January 1947 and the other is your number - C/JX 813267. In those days sentimental farewells on station platforms had not yet arrived. My parents and sister stood solemnly on the platform of Carlisle Citadel Station as I and another school-fellow left together on the same draft and with the same destination. John and I were able to share the first

nine months and though we were not close friends it was good to have someone from home to share a cabin with.

After a long cold journey we arrived at Corsham (outside Bath) to join H.M.S. Royal Arthur for our basic training. We had missed the evening meal but they laid something on - engrained on my memory are the chalk letters "Thick rich brown gravy." on the blackboard. Snow lay on the ground for the first three months and conditions were fairly horrific at times. The steel of a .303 rifle is very very cold when doing parade drill at sub-zero temperatures.

In those immediately post-war times, one had been conditioned not to complain over-much. If you developed flu (I did) you were given a beaker of castor oil to drink - kill or cure! My boots were not a good fit; and my instep got bruised and the skin broken. I had to wait until my first week-end leave after six weeks. My father was a dentist and he had had a delivery of this new fangled stuff called penicillin and wondered if it would help. The effect was miraculous.

Signal training school (H.M.S. Scotia at Lowton St. Mary's near Warrington Lancs) meant a six months course. I am a flautist and so got privileges by joining the camp voluntary band as a piccolo player. Band practice was a treat compared to the chores imposed on less artistic ratings. Most marching orders were based on the fleet signal book. The most popular command was "Item Jig Pennant Nine". This meant (I think) "unit to proceed according to previous instructions"; i.e. break off and speed to the NAAFI for elevenses. The instructors were senior Yeomen of Signals; who had all been through the war and many were near the end of their service time. One gradually discerned that in some ways we National Servicemen who were 'educated sort of blokes' could have a certain kind of understanding with the commissioned officer class which in certain circumstances by-passed the NCO's.

I remember there being an imminent Admiral's inspection; and I was never very good at laying out my kit. My divisional officer saw my poor efforts and said: "It's not very good, really, is it Vigeon?" I replied "No Sir !". No more was said, but that night the orders for the following day showed that I had been placed on special duty where the Admiral would not encounter me and thus not run the risk of having to show him my kit.

We also had a padre who had served in cruisers during the war, and as a member of the Cotswold landed gentry had considerable private means. He ran an Austin 12 for local work (I later became his driver/Yeoman), but had a Rolls-Bentley complete with Rolls trained chauffeur for long distance work - quite unheard of in the straightened days of 1947.

Those of us who had been altar servers were encouraged to carry on with those duties. This meant among other things that from time to time we were entertained to dinner at some expensive Cheshire hostelry - the "Bells of Peover" was particularly popular. There I learned how to send back a bottle of expensive wine and still be treated with due reverence.

On other occasions we were taken to Manchester Opera House, Manchester to see the out of town premiere run of some new fangled kind of show called "Oklahoma". I remember also a lieder recital by Elizabeth Schumann. Our Padre was on good terms with the Commander and milked the system for all he was worth. One Thursday morning he appeared at the early morning parade [6:45am] and saying "Today is Ascension Day. It is a holy day of obligation. There will be Holy Communion in the chapel at seven hundred hours. Those wishing to attend will be excused duties and will be entitled to a late breakfast". There was a not un-surprising rush of devotion among the ranks.

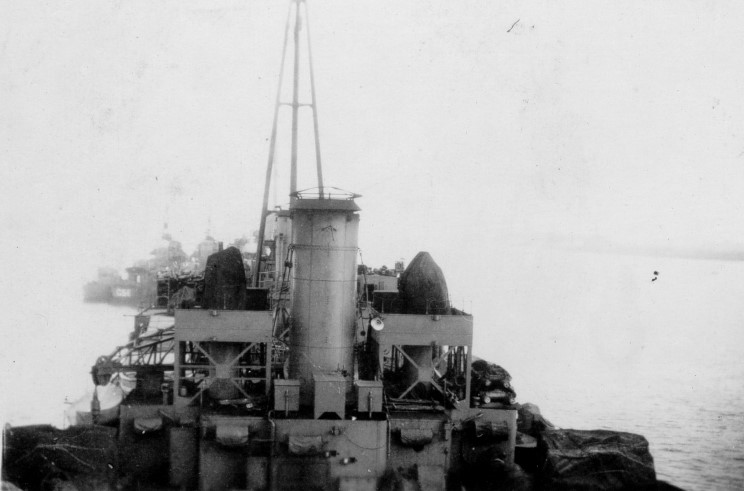

After training, I was posted to H.M.S. Anson, a battleship largely moored in Portland Harbour where with the King George V and the aircraft carrier Victorious it formed the Training Squadron where trainee professional seamen were given their first taste of sea time. I learned three important lessons;

[a] On runs ashore I discovered that I was someone whose limit was three pints. I could not get drunk on beer because after that I felt too ill to continue. On the other hand I discovered the over-riding morality of the navy - look after your shipmates. They always got me back on board on time.

[b] I discovered the perils of winning at cards. One night I couldn't fail at Pontoon and raked in a fortune at 1 penny a stake. I ended up over £1.00 in my pocket [multiply by approx 50 for today's values] and in a flush of generosity treated the mess to drinks all round. The following night I lost every penny I had won.

[c] How the services protect themselves. One stormy night the liberty boat for the Victorious was returning and in order to protect it from the gale, the coxswain took it to the after gangway which was on the lee side and normally used by the Officers. The Officer of the Watch swore at him and ordered him to get away from the quarterdeck and go to his proper place. As the boat went round the stern it met the full force of the wind, capsized and dumped the ratings in Portland Harbour. One at least was drowned. All the lower deck in the squadron were up in arms about a disaster caused by the class system; we reckoned that officer was guilty of murder. There WAS an enquiry, but I seem to recollect that the publicity was muted. If it had happened today I am sure 'The Sun' would have had a hey-day!

Some personal anecdotes; At sea, preparing for anchoring, I was working with "Badger" our 'mess killock" - a three badge Leading Signalman who was 'no better than he ought." Suddenly he said to me ; "You know "Vig", the blokes in the mess don't like to hear you swearing." "Well YOU all do" I replied, "so what's the difference ?" "Ah !" he said, "but you go to church. We expect something better from you." That was a sermon which has stayed with me all my life. I also remember the same man saying during a mess discussion on religion. "I can't see the point of going to church and saying prayers on a Sunday. But I say prayers when I need to. In the last year of the war when we were being attacked by Kamikaze pilots in the China Sea, I saw one coming straight for the bridge and I said "O God, let it miss !" - and it did." (What you might call practical religion.)

In 1948, there was a "scandal" let by the Daily Express about the run-down of the Royal Navy. "Home Fleet reduced to One Cruiser (the Super B) and Six Destroyers !" was the headline. As an exercise in public relations, the Admiralty put to sea every ship that would sail for some maneuvers in the North Sea (Operation Dawn). We were all below strength and under-trained for such fun. After the exercises, we were steaming in fog up the Forth on the way to Rosyth, with our sister ship - the "Howe" - astern. Suddenly the radar plot shouted that they had lost contact with Howe. The Navigator rushed to the radar screen and the report was correct. "There's only one place she can be" he said, "THERE !" - and he pointed to the centre of the circle (which was of course 'us'). At that point

there was a shout from the stern look-out and the Howe appeared out of the fog and crossed just a bare cable length from our stern . It could have been one of the great classical naval disasters, but happily the great ships just missed. We immediately anchored and waited for clear weather.

Two good examples of the 'special relationship' which occasionally manifested itself between officers and national service ratings. 1. The Admiral was having a drinks party for the King's birthday. His Flag Lieutenant was of course his social secretary. He had also - as Squadron Signals Officer - to send an important signal. I was on duty in the Bridge Signal Office on my own - we only had a 'destroyer ships company'. The phone rang:

"Vigeon come down to my cabin and collect a signal." When I got there "Flags" was at his wits' end. There was a lot of noise from the Gun Room where the Midshipmen were also enjoying their own party. In his best naval languid tones he looked at me. "Vigeon, will you kindly go to the Gun Room, ask to see the Duty Sub-Lieutenant [the mess president], present him with my compliments and ask his young men to bloody well shut up." It was with the perverse sense of pleasure that such occasions give that I did as I was asked. The Sub-Lieutenant eventually appeared with a large pin gin in his hand, and in best Dartmouth tones said "Yes - what is it ?" I slammed to attention. "Flag lieutenant's compliments sir, and will you please ask your young men to bloody well shut up." There was nothing he could say, and the moral superiority of the national service lower deck was reasserted!

2. I was on the Anson when she was the guard ship for the Olympic Regatta at Torbay 1948. There was a variety of warships of many nations in attendance. A French destroyer called us up on light with a message

in English inviting our Captain to drinks. I got some kudos from my colleagues because when we couldn't read the Frenchman's morse all that clearly, I was able to ask them to repeat 'le mot apres'. The Skipper (Capt. David Orr-Ewing, D.S.O., R.N.) felt that he ought in all politeness answer the message in French. In desperation he said to the Chief Yeoman. "Anyone on the staff speak French, Chief ? " "Well," came the reply, "there's Vigeon, Sir, he seems an educated lad." "Ah yes! "said the Captain,"and with a name like that he must be a Channel Islander." I'm not (a Channel Islander), but I had done Sixth Form French. So an Ordinary Bunting-Tosser sat down at the table with a Four ringer Captain and together we wrote down "J'accepte votre invitation avec grand plaisir ".

Later on my last day on the Anson, I was given the privilege of raising the white ensign at morning divisions . As I tidied everything up at the end of the ceremony, the Captain walked over with the remark "I hear you are leaving us today, Vigeon" and we had a brief conversation about my future plans for demobilisation and the benefit of history degrees at Cambridge. It was a nice gesture which I appreciated.

I was due to serve the statutory two years service. But in 1948 the Berlin crisis erupted. One night when I was on solitary duty in the signal office, a coded message marked Top Secret came through. I had to call in the Communications Officer to decode it. It was a very small office. He sat down with his code book and the type writer. He turned round, smiled and I could swear winked at me. "You are not, of course, Vigeon, reading this."

"Of course not sir," I replied. I had already seen the message which was to the effect that as from January 1st 1949, all National Service men would be required to serve an additional three months until the emergency had passed. This was not to be announced until some weeks later. Somehow I resisted the invitation to share my secret. To be able to think to oneself "I know something you lot don't know" is a strangely satisfying feeling!

All the signal meant to me was that I left HMS Anson as planned and they had to find something for me to do for the next three months. This turned out to be the supreme waste of being on the staff of Senior Officer Reserve Fleet Harwich, where HMS Tyne (later it was the Woolwich), a submarine depot, ship sat on the bottom at low tide and leant to port or starboard as the mood took her. Almost the only thing I remember of those wasted weeks was when one of our number went on leave to get married. Somehow someone had got a note of his address for the wedding. So together we cobbled together the greeting "PCS 2359". The operator who took the message was suspicious but could not prove anything. She was of course correct. The signal reads "Report position course and speed at midnight".

So the end of my service was 'not with a bang but a whimper'. Not that here had been any bangs anyway. But in retrospect I am grateful that I had that time on the lower deck before I had discovered my vocation to the priesthood. It was good for me to have the opportunity of mixing it with a wide variety of men and without the subsequent protection that the 'benefit of clergy' can give. If you can climb the foremast of a battleship in a force 8 channel gale to free tangled bunting, then you don't need to doubt your masculinity or your ability to cope. Somehow in retrospect, I forget the boredom and the harshness and the nonsense and the cold and all those times when one cursed one's lot and I have always said since that I enjoyed the experience. I must be mad.

-Reverend Owen Vigeon (ret.)